“It is not real art. It is a screensaver.” You have probably heard that before. The sceptics are quick to dismiss anything that lives on a screen. The same detractors once brushed aside street art, and before that, folk traditions. Is it only what is inside a white cube that counts as art? Sometimes, almost without noticing, we end up carrying that bias ourselves.

Yamini Telkar thinks differently. She has spent more than thirty years with auction houses, private galleries and academia. When digital art began to take shape as a medium, she chose to look closer instead of looking away. Through ArtKyk, the platform she co-founded, Telkar has worked to reimagine art away from exclusivity. Telkar now curates an exhibition titled An Invisible Bind where NewArtX and Gallery Sameksha come together, bridging the gap between traditional and digital art. This group show features five emerging artists, all of whom are women from across India, presenting works in various mediums including painting, mixed media and sculpture. Notably, each artist will debut a new digital artwork, developed in collaboration with NewArtX. The exhibition explores themes of collective identity and emotional connection, stemming from an artist retreat and collaborative introspection. Leading up to the opening of the show on 22nd August 2025, Telkar reveals what shapes her curatorial practice.

Video Courtesy: Nirali Lal, Look Straight / Look No Further, 2025, NewArtX.

Namrata Dewanjee (ND): What is the landscape of digital art in India right now?

Yamini Telkar (YT): Every time a new technology arrives, it is met with suspicion. Two groups form. One predicts doom and claims creativity is taken over by machines. The other is optimistic. Digital art has been around for decades. In the 1960s and 70s, artists were already experimenting with it. The level of intervention varied, but it was not new. What has changed now is access. It is becoming widely available. Baiju Parthan was one of the early artists in the 2000s who made digital work for online audiences. Ranbir Kaleka brought technology into his paintings and installations. These examples show a slow but steady integration of technology into the art world.

Image Courtesy: Vadehra Art, Ranbir Kaleka, Conference of Birds and Beasts, Duratrans print mounted on light box, 2010.

Galleries and museums still treat art as a fixed object, expecting it to last in an unchanging form. Digital art challenges this. CDs were once popular. Now, laptops do not have CD drives. Technology keeps shifting. Once we accept that digital art behaves differently, it becomes easier to value it. But digital art is here to stay. What is the intensity of it? How much is it going to pervade the art market? Only time will tell. But what I do believe is that it is going to be a part and parcel of visual language, especially as it can be made accessible to a wider audience. It can be made available to people on their terms. So you don’t have to go to a gallery or a museum to see it. Artists can rework earlier versions as technology evolves. That is its fascination.

ND: People often imagine art inside a gallery, within the white cube. That space has long defined what is seen as high art. How do you negotiate this divide between art that lives inside the gallery and art that exists outside it?

YT: The gallery, the white cube, creates a certain association. It links art to market value, perception, pricing, and the idea that art will appreciate over time. There are two ways to look at this. One is that as the artist matures, experiments, and develops their visual language, prices rise. The other is that art has long been seen as a tangible object with inherent value because it can be traded.

Digital and multimedia art shift this. They are not tangible in the same way. You cannot hold them. They may be projected into a room, but only at that point in time. This removes one strong association: the canvas that is the object. The question becomes: what is the value you are paying for, and how does it appreciate? It is a complex discussion. There is also another layer, which is social and political. Cryptocurrency is not recognised in India. In other parts of the world, it is. That difference shapes how digital art circulates in the market. Still, if we set aside that financial layer, the question remains of how to establish digital art within the ecosystem. When a work enters museums and collections, legitimacy is built. Digital art is still finding its way into that pathway, and that is the struggle it faces and we are looking at creating negotiation that support the digital art. NewArtX for instance has set a good precedent in this matter, they work in block chain technology for digital art works but deal in only a fiat currency which is obviously not crypto and a legal tender. This gives collectors, artist and art enthusiast a sense of security to invest in digital art.

Video Courtesy: Shalini Dam, Love Letters, 2025, NewArtX.

ND: Speaking of galleries, tell me about your new show with NewArtX at Gallery Sameksha.

YT: Sameksha sits in a space with an interesting legacy. It began in 1991 as an offshoot of IILM, the Institute of Integrated Learning and Management in Delhi. The idea was to nurture art, not just visual art, but also music, dance, literature, poetry and prose. The pandemic stalled things, but now they’re keen to revive that original vision, with a focus on nurturing younger or mid-career artists rather than only chasing big names. NewArtX played a crucial role by removing practical constraints for artists who are not well versed with digital tool, allowing them to focus purely on ideas. By guiding what’s technically possible, the platform enables exploration and expression through collaboration. Over the course of developing the artworks for An Invisible Bind, this support helped the artists to push their work into new, innovative directions.

So instead of a standard group show, we decided to think differently. We brought together five artists, all of them being women from across the country, working in diverse mediums: painting, sculpture, ceramics, digital, even poetry. Rather than handing them a theme and asking for finished works, we organised a kind of camp. For seven days, they were asked not to bring materials, not to paint or sculpt, but simply to talk. Every day, debating a simple question: what does it mean to be a contemporary artist?

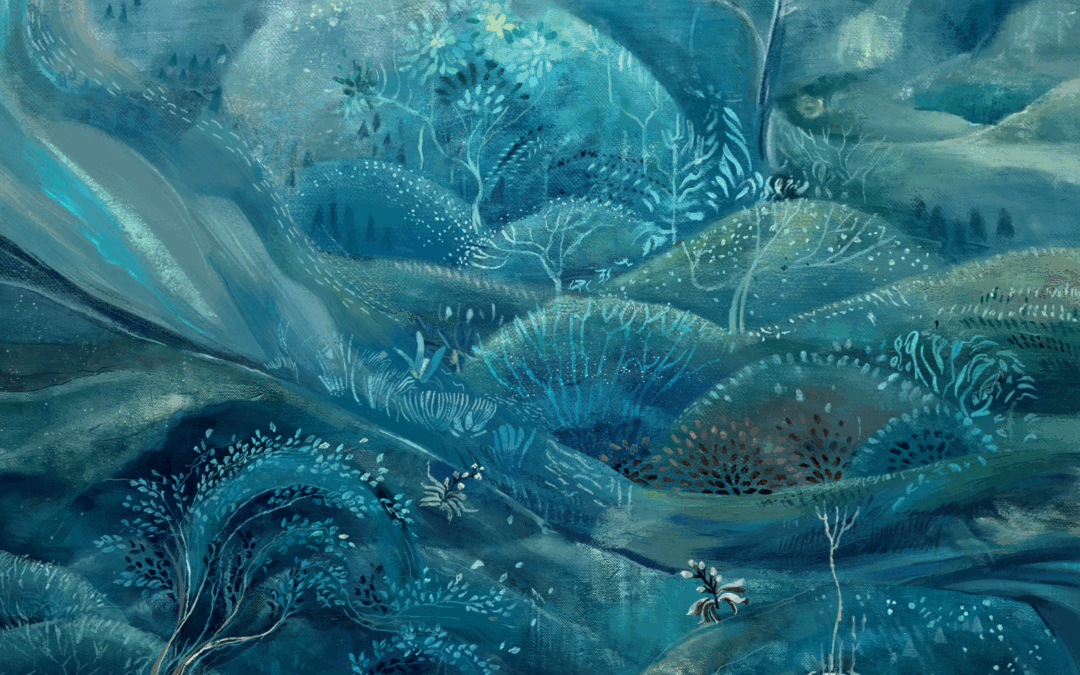

By the end of those conversations, they understood each other’s practices in a deeper way. Bonds had formed, context had been created. Only then did I set the brief: each artist had to make one work in a medium new to them — digital. Some had never tried it before, but with support provided by NewArtX on the execution, they began to translate ideas into unfamiliar forms. Teja Gavankar, a trained painter who now works in sculpture. Tanya Mehta, who works digitally but roots her themes in Indian texts. Shalini Dam, who explores ceramics as objects experienced in space. Nirali Lal, who moves between painting and poetry. Vanita Gupta, who expands her paintings into almost sculptural forms. Each responded differently, but what connected them was the questioning, and it comes across in the digital works with NewArtX the most, interestingly, because that’s where they’re thinking differently about their subjects. They’re not thinking in terms of the practicalities of the work because that’s taken care of by the NewArtX. And the artists are full of ideas and they share them with the digital team and then they come back with what is possible and how to make it work. The weeklong conversations resulted in an expression that is outside of the artists’ usual purview of work. And this happened in a very seamless way. It will be fascinating to see how this experience shapes their practice going forward.

Video Courtesy: Teja Gavankar, Allomother, 2025, NewArtX.

ND: You mentioned that NewArtX helps artists execute their ideas. David Hockney once remarked to Anish Kapoor that he has a whole studio working for him, so it’s not really Kapoor’s work alone. How would you respond to that critique?

YT: For me, the idea is what matters most. Skill can be taught, thought cannot. What compels me to make an artwork my way is something only I can bring through my experiences. Skill is the foundation, but without vision, it becomes formulaic. The separation comes when thought and essence drive the work. That’s what makes it art, not just execution.

ND: How would you define digital fine art?

YT: I have a problem with the term fine art.

ND: Why is that?

YT: It took me a long time to move away from that construct. In art schools, you have a fine art department, you have art and craft, and you have architecture. But why? These divisions are useful in education and communication, to position things. You cannot call everything art, or it becomes confusing. But beyond that, they should not matter. It is like wearing a saree. For someone who does not know much about textiles, you say it is a saree. Later, if they are interested, you can explain whether it is made on a handloom or a particular weave. But at the end of the day, it is still a saree.

For me, the important question is what we call an artist. Is it someone with a creative inclination, or someone who can express themselves in a creative way? That expression may take many forms but the foundation is the same. Some artists are trained academically and define themselves by that. But many are not. M.F. Husain never went to art school. Bhupen Khakhar did not study art formally. Many younger artists also fall into this space. Yet they are very good at what they do. And then there are artists like Jangarh Singh Shyam from the Gond tradition. Just because he came from a tribal background, should his creativity be confined to that label? Identity can be convenient. Sometimes you use one part of it, sometimes another. But labels do not capture the whole picture.

Video courtesy: Vanita Gupta, Acts of Escape and Return,2025, NewArtX.

At Bengaluru Airport, this collapse of categories is visible. You see photography, sculpture, antiques, traditional art and contemporary work. For example, the golden flying figures hanging from the ceiling. People say it is Kinnala art. But Santosh Kumar Chitragar, who made them, studied fine art at Chitrakala Parishad. He then returned to the craft of his family. So what do we call him? A trained artist? A traditional artist? Both?

At the end of the day, art is art. Whether made digitally or by hand, if it communicates or makes you think, then it works. But the complications arise with AI. Where do the images come from? What about originality and copyright? Those are real concerns.

ND: There’s always the question of high culture versus low culture. Street art, for example, is often dismissed as not “real art.” The same with digital art. What was the hardest part for you in bringing digital art into your curatorial practice?

YT: I got a lot of that. Someone once said, “So what’s new about digital art? Even I can do it.” And I replied, “Yes, but you didn’t.” That’s the point. My challenge was always to break rigid divisions. Bengaluru, as a tech city, made digital art in the airport context easier, but the bigger challenge was in the works we showed. We had a simple video piece, and then Sarwesh Shah’s generative program based on the Yakshagana dance. He stripped away the costume and the stage, showing just a single figure moving across a black screen. Suddenly, the performance became about space and presence. Another artist built images with hundreds of layers and linked them to a weather app. Sunrise, monsoon, full moon and the artwork shifted with real time. The lesson is: it’s never just about technology. The tools are available to all, but what matters is the idea.

VIDEO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FL2Jt9aAUvA

Sarwesh Shah, Trails of Yakshagana, digital, 2023. Image courtesy: Kempegowda International Airport Bengaluru

ND: Tell me about how your story began with art. Where did you start?

YT: I’m the third generation in my family to go into art. Everyone else studied applied art, so my “rebellion” was studying fine art. I trained as a painter, but soon realised I loved teaching, writing, and curating just as much. I worked with SaffronArt from 2000, studied at JNU, worked in galleries, curated for Mumbai Airport, and eventually started working on the Bengaluru Airport art curation in 2019. So I’ve seen the art world from many angles, be it academic, commercial or curatorial.

ND: You’ve been around technology for a while. Have you seen people’s perception of it change over the years?

YT: Yes and no. Earlier, there was resistance. People wanted printouts, not digital images. Now there’s acceptance, but still on the surface. Digital art can democratise access. Think of Raja Ravi Varma: he chose 25 paintings to make into prints, reaching the masses. Digital art can do that today, but without suspicion around duplication. Each work can still be unique. It can also reach beyond metro cities. With mobile networks in 97% of villages, why shouldn’t smaller towns have access to art the way they already access education or entertainment?

Image courtesy: The Hemamalini and Ganesh Shivaswamy collection, Bengaluru, Raja Ravi Varma, Oorvashi, chromolithograph, 1896.

ND: Why is accessibility important to you?

YT: Because audiences are small. Galleries complain people don’t come, but also intimidate them with locked doors, dense wall texts and jargon. Accessibility isn’t about dumbing down. It’s about telling the story in a way that excites and connects, without reducing the artist’s thought. Even small changes like friendlier spaces and clearer language can make a big difference. Artists want wider audiences, and galleries need them too if the market is to grow.

ND: What do you think people should take away from the new exhibition and this collaboration between Gallery Sameksha and NewArtX?

YT: The value of experimentation. By pushing artists into digital media, we gave them the chance to rethink their practice. The conversations of those seven days, their openness, their questioning, their support of each other, were as important as the final works. I hope visitors see that community and thought can be just as powerful as the finished object.

Featured image courtesy: Vanita Gupta, Acts of Escape and Return,2025, NewArtX.

0 Comments